The DyckmanDISCOVERED initiative

investigates the stories of enslaved people who live and worked on Dutch farms in what is now called Inwood. This initiative brings an inclusive history to the community, fosters a sense of transparency and, we hope, engages visitors who have not seen themselves represented in the current narrative.

With a grant from The New York Community Trust, DFM hired a part-time research assistant to uncover truths about the people who worked on the Dyckman Farm and the other farms nearby. With new information, DFM designed new educational materials for the museum, created public programs and engaged local artists to produce site specific installations that communicate the story of these underrepresented people. This project reinforces the importance of inclusive historical narratives in America’s historical institutions, of all sizes.

DyckmanDISCOVERED with Untapped New York

DFM’s Executive Director Meredith Horsford gives a virtual talk about the DyckmanDISCOVERED initiative.

DyckmanDISCOVERED with The Gotham Center

DFM’s Research Assistant Richard Tomczak discusses the findings of the DyckmanDISCOVERED initiative.

SUPPORT OUR RESEARCH WITH NEW MERCH

Support the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum by purchasing a limited edition design that highlights the enslaved and free people who lived and worked at the Farmhouse.

Proceeds support further research and educational programming on the topic of the enslaved and free people highlighted on the products.

Make a purchase today to help us support DFM research and free public programming!

DISCOVERIES

As we continue our research, we are making discoveries about the lives of the enslaved and free peoples who lived in the Dyckman Farmhouse as well as on neighboring farms. While much research is still being undertaken, we would like to share what we know about the lives we are learning about.

SLAVERY IN THE NORTH

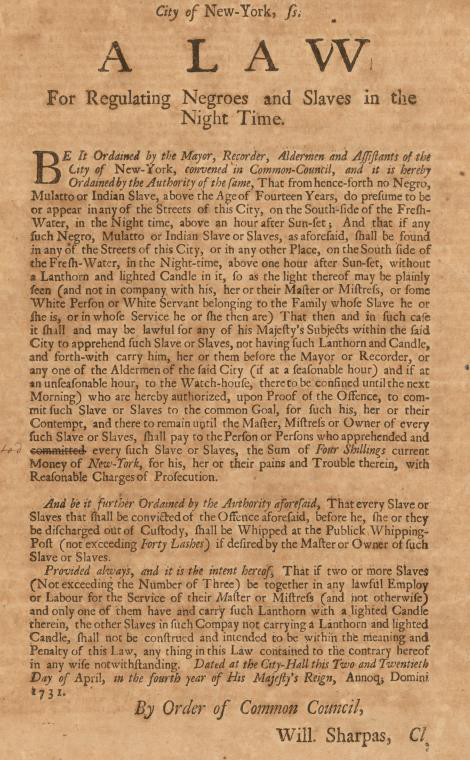

Slavery was by no means only in the South. Northerners had their own system for integrating enslaved people into the economy and had their own ways of isolating them from all forms of social and economic mobility.

Slavery was introduced into this area by the Dutch in 1626. There was much land but a chronic shortage of people to work it. Between 1700 and 1750, the enslaved population in New York grew faster than the white population. By mid-century, New Netherlands was the largest slave colony in the North.

The Dutch West India Trade Company had few regulations relating to slavery. Northern laws were more lenient towards familial connections and pay. Slavery in the North, however, was still implemented by force and abuse. Laws and regulations surrounding slavery became strict during British rule in the North.

Slavery in New York State ended in 1827, yet traces of it survived until 1841.

Just as slavery in the North differed from slavery in the South, rural slavery , including the Dyckman Farmhouse at the time, was very different from slavery in urban areas. In rural New York, the enslaved performed agricultural labor and other highly-skilled work.

New York farms were self-contained units in which the enslaved members of the household had to be able to grow crops, as well as tend to livestock, do carpentry work, make clothing, clean, cook, and be caretakers of children.

Enslaved were often bilingual, if not multilingual; they spoke Dutch, English, French, and their native language.

Shortly after the still standing Dyckman Farmhouse was built, there were seven to eight enslaved people living there.

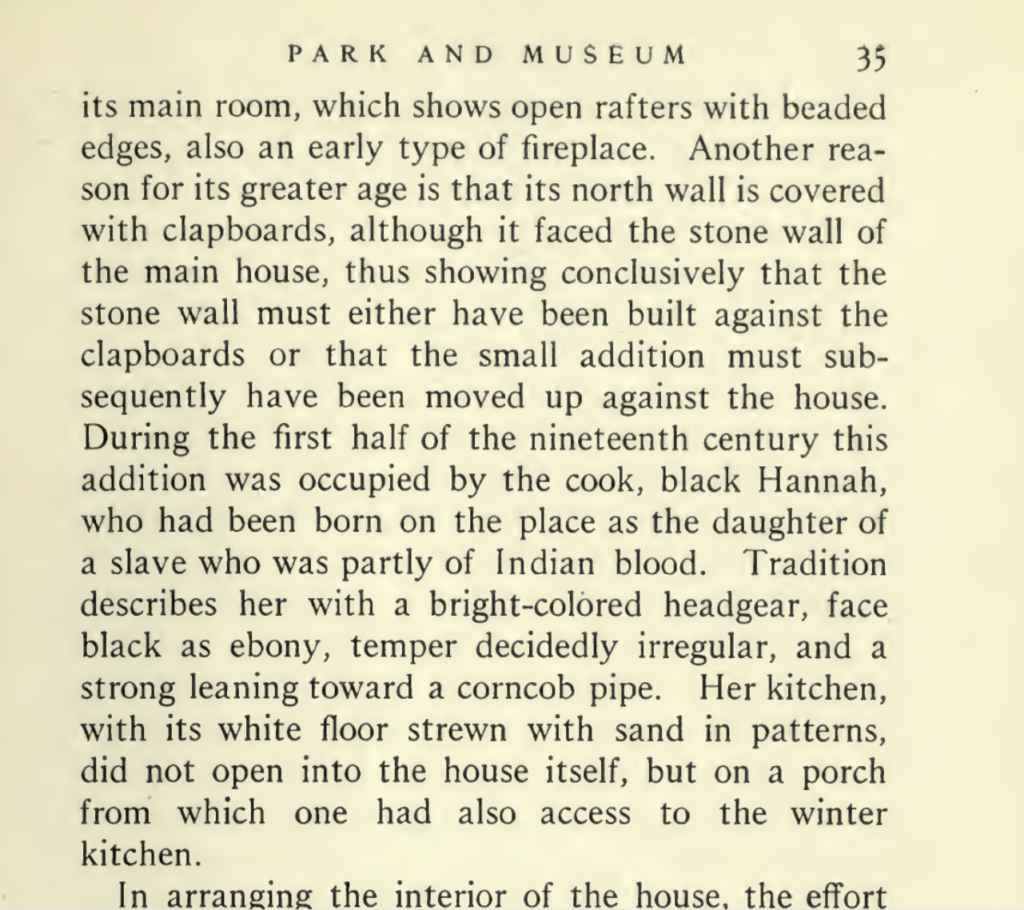

HANNAH

Dean, Bashford and Alexander McMillan Welch. Dyckman House Park and Museum 1783-1916. NY: 1916, p. 35

Family tradition tells of a free black woman named Hannah who lived with the family and worked as a cook. Based on those stories we believe she was living in the farmhouse in 1820. According to census records, Hannah was born between 1784-1794 which would make her between the ages of 26 and 36 in 1820. A 1917 legislature states the following: “the cook, black Hannah, who had been born on the place as the daughter of a slave who was partly of Indian blood. Tradition describes her with a bright-colored headgear, face black as ebony, temper decidedly irregular, and a strong leaning toward a corncob pipe.”

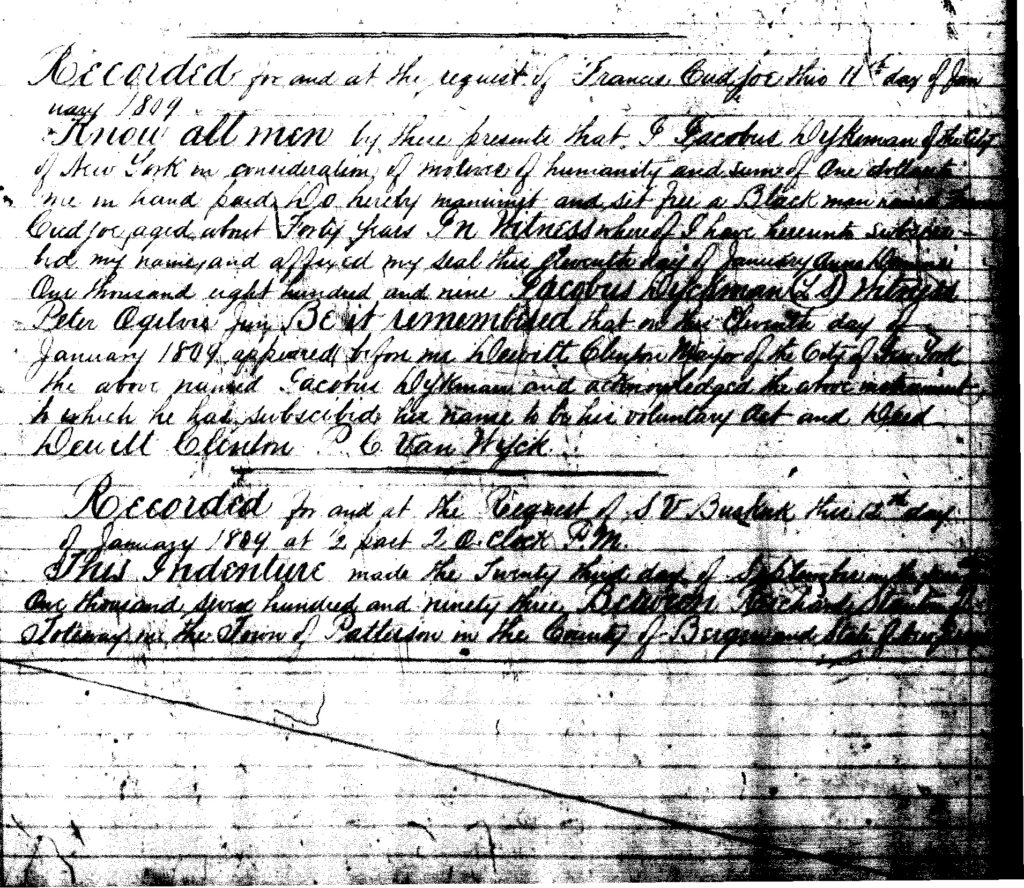

FRANCIS CUDJOE

The only enslaved person that we know of by full name in Dyckman family history, Francis Cudjoe was manumitted in 1809 by Jacobus Dyckman. He lived and worked on the farm roughly a decade prior to Hannah, but their time at the farmhouse may have overlapped.

Know all men by these present that I Jacobus Dyckman of the City of New York on consideration of motive of humanity and sum of one dollar to me in hand paid Do hereby manumit and set free a Black man named Francis Cudjoe aged about Forty years. In witness whereof I have hereunto subscribed had my name and affixed my seal this eleventh day of January Anno Dominis one thousand eight hundred and nine. Jacobus Dyckman, Witness Peter”

1809 emancipation record for Francis Cudjoe (b. 1769) who served Jacobus Dyckman (son of William) at today’s standing farmhouse property

WILL

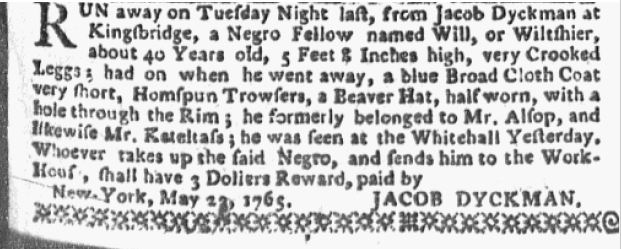

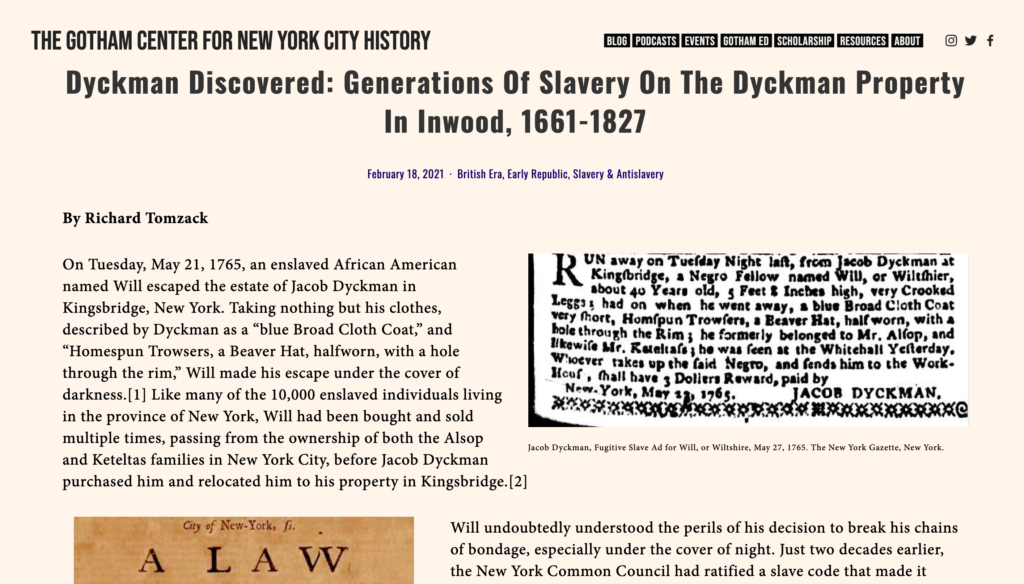

The person we have the most visual description about is a man named Will through a runaway slave ad. These ads were known to be full of detail including phenotypic appearance, clothing, languages spoken, and talents such as playing an instrument.

A May 1765 runaway slave ad placed by Jacob Dyckman of Kingsbridge for a 3 dollar reward for Will described as “A Negro Fellow named Will, or Wiltshier, about 40 years old, 5 feet 8 inches high, very Crooked Leggs; had on when he went away, a blue Broad Cloth Coat very short, Homespun Trowsers, a Beaver Hat, half worn, with a hole through the Rim.” Will was the enslaved of Jacob Dyckman, owner of the Black Horse Tavern and the brother of William Dyckman who built today’s standing farmhouse. He is also the father of Garret and Staats Dyckman, who we also have records of their enslaved.

GILBERT HORTON

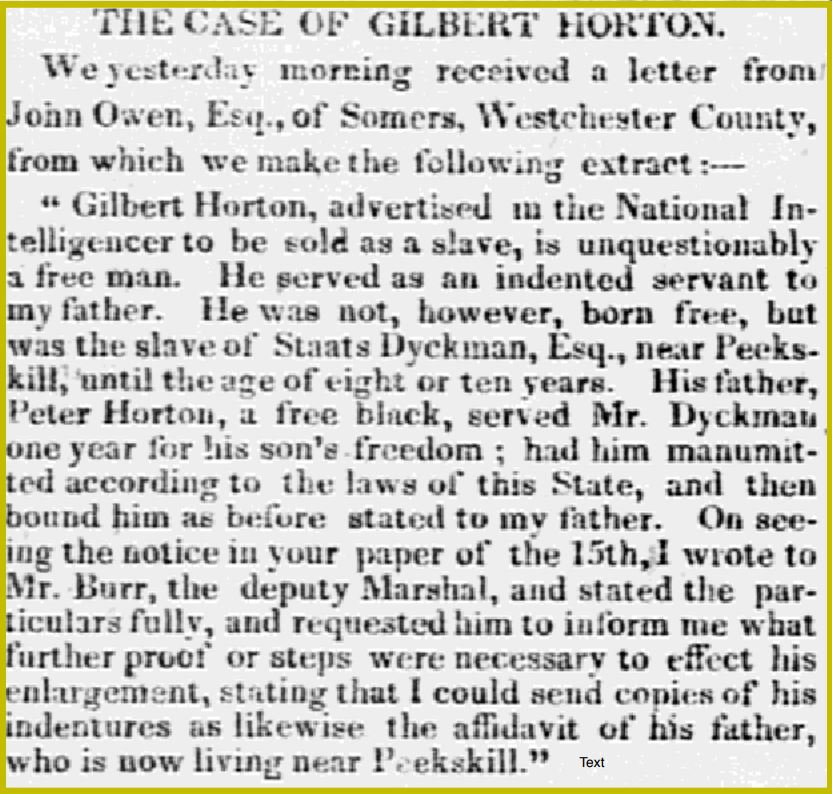

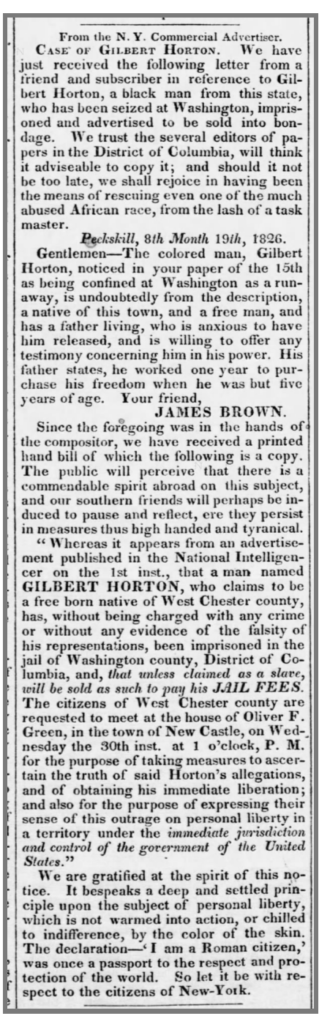

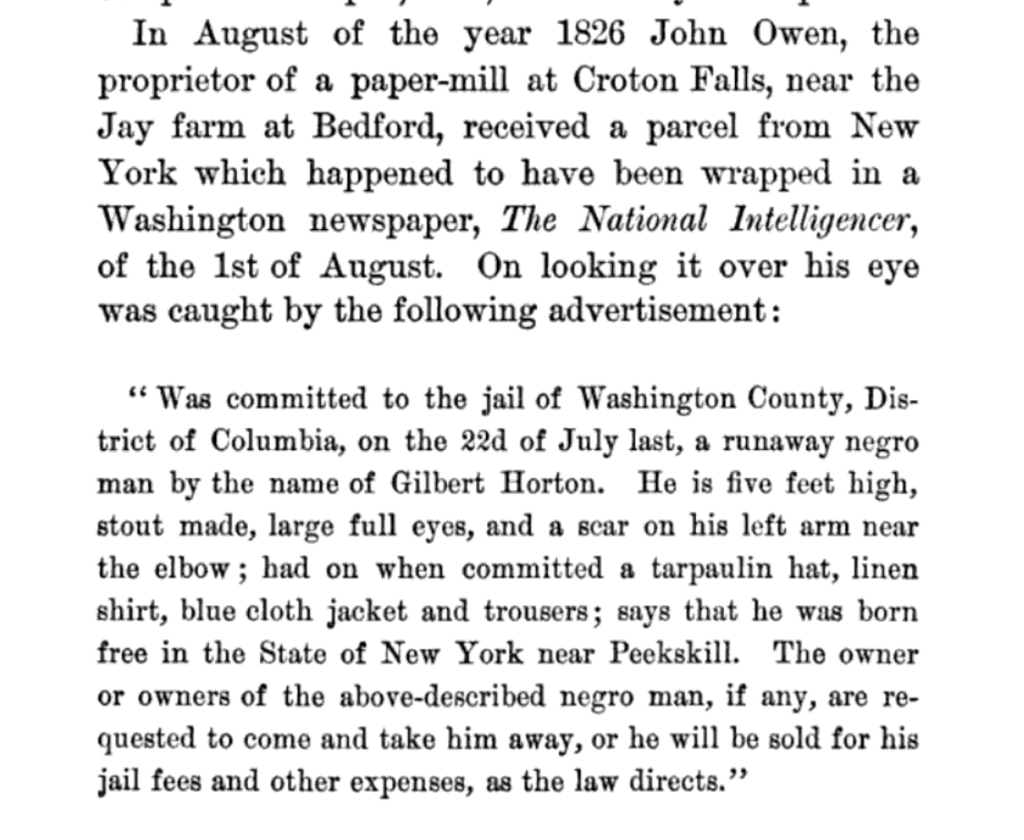

We have discovered copies of two news articles pertaining to Gilbert Horton, an enslaved of Staats Dyckman. An Aug 1826 article stated he was found, imprisoned, and was to be sold. Soon after, this was countered by a Sep 1826 article stating he was a free man who had served Staats Dyckman and was manumitted after his father Peter Horton served Staats for one year for Gilbert’s freedom.

HAREY

Harey was 32 years old when he was freed according to an 1809 emancipation record for “mulatto” Harey (b. 1777) who served Garrett Dyckman, brother of Staats.

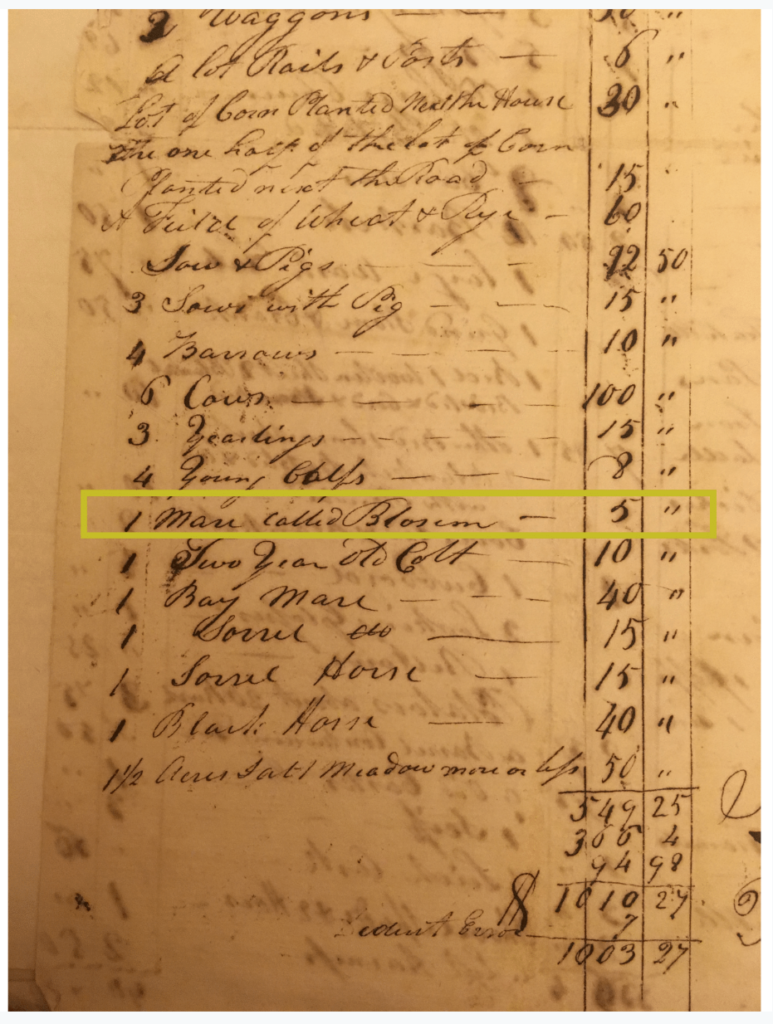

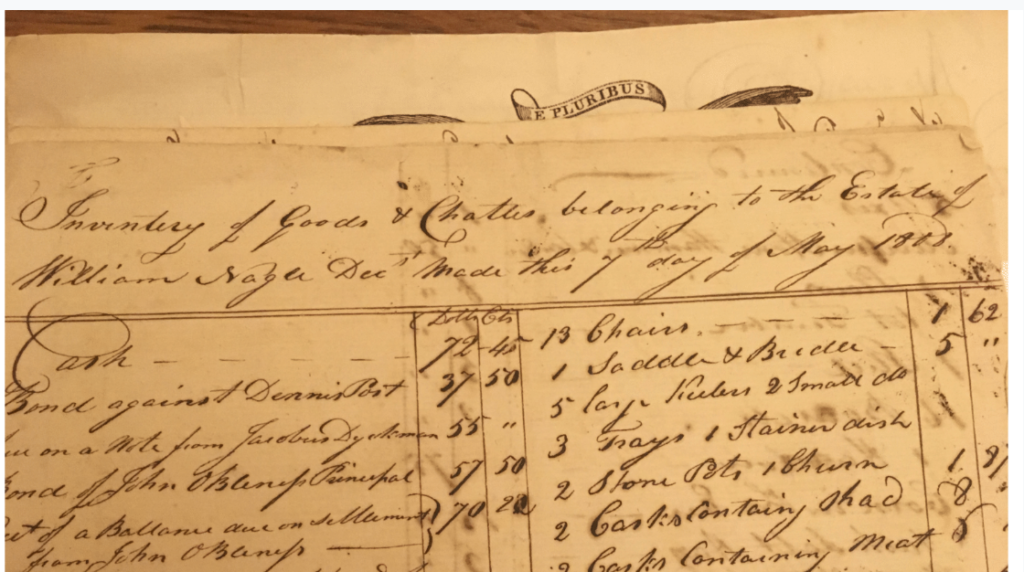

BLOSSUM

An 1808 estate inventory of a Dyckman household listing various pigs, cows, horses, and “1 man called Blossum.”

Through recent research, this inventory of William Nagel possibly reads, “1 mare called Blossum.” Following Blossum is a “A Two Year Old Colt” for $10 then “A Bay Mare” is listed for $40. Prior, 6 cows for $100 is listed, therefore it is unlikely a man named Blossum was equated to $5. That said, the enslaved were often listed on inventory sheets alongside livestock. This is currently under review.

INWOOD SLAVE BURIAL GROUND

H. Dorothea Romer’s “Jan Dyckman and Descendents” text tells of the location of a burial ground behind the previous farmhouse homestead: “for years after Jacob’s marriage the two families lived in the Dyckman house together. The Burial Ground lay immediately behind the house, and in unhallowed ground beyond, were the graves of over thirty family slaves”. Today, this is located at PS 98’s faculty parking lot on 212th St. between Broadway and 10th Ave. The graves were dug up and destroyed during the progress of urbanizing Upper Manhattan in the early 20th Century.

Bolton quote: “The remains of these humble workers of the past reminds us of the time when, even in this neighborhood, the practice of slavery was customary. Perhaps no other relic of the past could more decidedly mark the difference between the past and the present than the bones of these poor unwilling immigrants, whose labors cleared the primeval forest, cultivated the unturned sods, and prepared the way for the civilization that followed…”

TALKING ABOUT RACE MATTERS LECTURE SERIES

A series of talks with experts each looking at the topic of race from a different perspective and touching on a unique New York Black experience followed by a Q&A.

Head to our Talking About Race Matters event page to register today!

COMMUNITY CONVERSATION

Inwood Library:

August 2018 Press Conference:

In the Press:

NY1 – Upper Manhattan Residents Look To Honor Old Slave Burial Ground

90.7 WFUV – Former Manhattan Slave Burial Site is Memorialized

WCBS 880 Radio – State Senator Launches Effort To Memorialize Inwood Slave Burial Ground

News from the Office of Senator Marisol Alcántara – Slave Burial Ground in Inwood

ARTISTS

2021/22 — I Was Here

2020 — No Records by Reggie Black

2019/20 — Peter Hoffmeister’s Ground Revision

Our artist exhibitions are made possible in part with funding from the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone Development Corporation and administered by LMCC. UMEZ enhances the economic vitality of all communities in Upper Manhattan through job creation, corporate alliances, strategic investments, and small business assistance. LMCC serves, connects and makes space for artists and community.

DyckmanDISCOVERED is made possible by funding from The New York Community Trust.